Forgotten Places

Stay Wild

Endangered Folk Art Sites

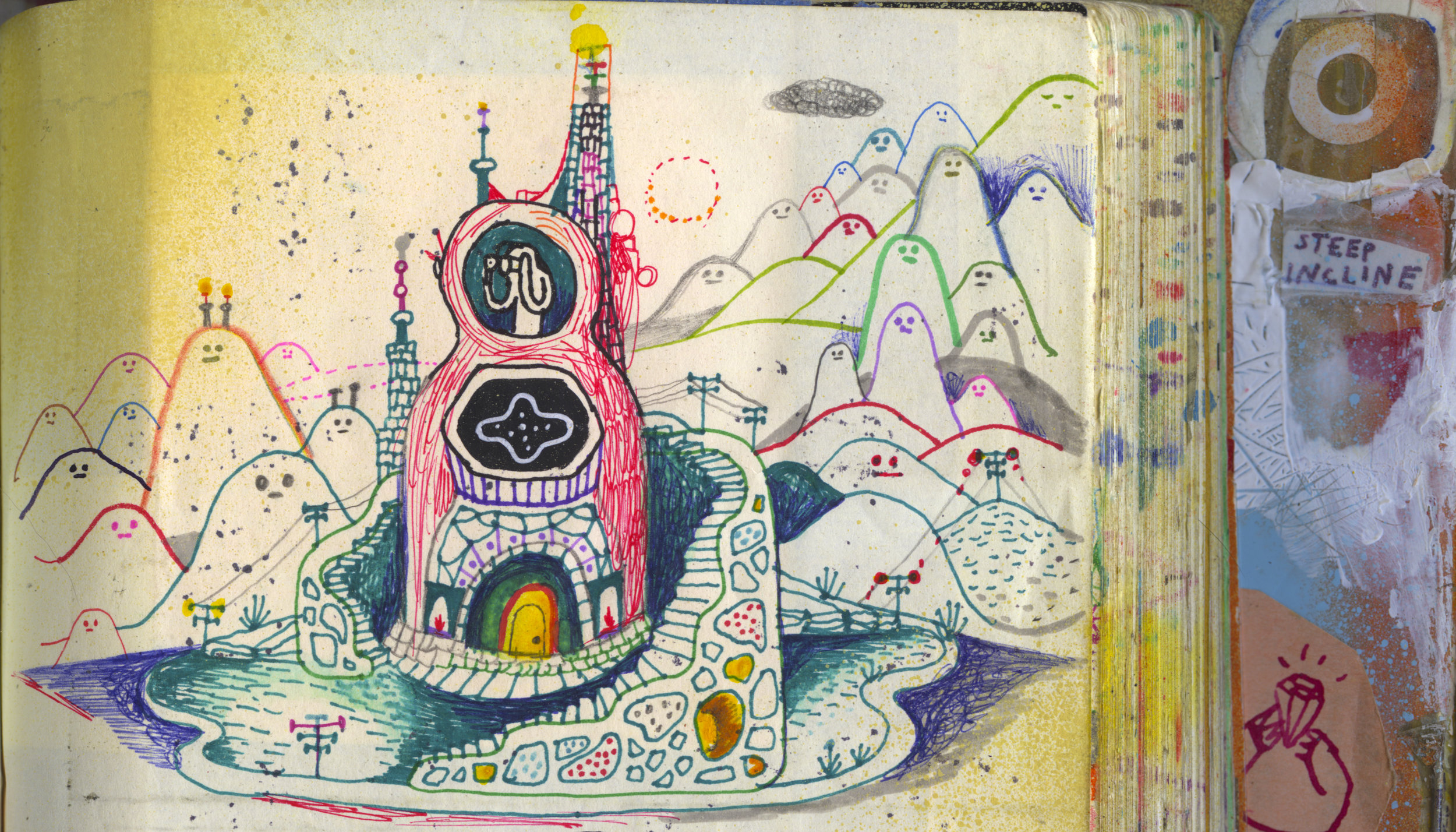

Photos and Artwork by Souther Salazar // @southersalazar

Story by Monica Choy // @choybot

My partner Souther Salazar and I got a wild hair and created a community art project called The Trading Tortoise which led us all over the U.S. and Canada for six months. Involving a tortoise-shaped tent, special objects, trading, and sharing stories by memory, we wanted to see what would happen if we considered objects to be symbols of memories rather than monetary value. Would people want to trade their objects and stories for ours?

Maria Cotera and Jason Wright, friends we were staying with in Ypsilanti, Michigan, suggested we visit various folk art sites across the country. We had stopped at roadside attractions before, and I knew about naive art, but I didn’t get their insistence that we must visit folk art sites. I was working on my own weird art, but was used to thinking of art as existing in galleries or museums, apart from day-to-day life.

Jason decided to drive us to sites around Detroit, showing us why folk art sites are important. Our first stop was a block-long art environment called the Heidelberg Project. In the 1980s, Tyree Guyton transformed abandoned houses where he grew up on Heidelberg Street up into sculptures. With his grandfather Sam and neighborhood children, he used paint and junk from trashed lots and houses, transforming a forgotten place into art and a symbol of resilience for the community.

We then visited Dmytro Szylak’s backyard, also known as Hamtramck Disneyland. This colorful display of handmade whirligigs, Christmas lights, wooden cut-outs, and found objects towering 30 feet tall can only be seen from the alley behind his house.

Our last stop that day was Silvio Barile’s Italian American Historical Artistic Museum. Silvio was in the back of his pizza-shop-turned-museum on a sweltering summer day. Seeing visitors, he put on a short-sleeve button-up shirt, which he left unbuttoned, greeted us with a round belly, and happily gave us an impromptu tour.

Silvio immigrated to the U.S. as an Italian refugee during World War II and opened a pizzeria. To commemorate the beauty and history of his native Italy, and in response to the commercialism and materialism he saw in America, he built his museum. The walls inside the restaurant are plastered with collages, toys, and handwritten signs about morality, Rome’s greatness, the importance of family, and Catholicism. In the patio behind the pizzeria stands his first cement sculptures, 10-12 feet high, painted colorfully, and studded with trinkets and broken tiles. Across the alleyway, Silvio’s sculpture garden holds 50 years of hand-built works three times the size of those at the pizza shop: figures of Athena, Caesar, and remakes of the Roman Colosseum and Statue of Liberty. These stand alongside figures of his family members, American presidents, the Three Stooges, and a monument to Maschio, a pig Silvio raised as a child. Our minds were blown!

After that day, we found ourselves detouring dozens of miles during our trip to visit folk art sites. The Orange Show in Houston, an ode to creator Jeff McKissack’s favorite fruit, was a personal favorite: a neatly-constructed park with brightly colored mosaic messages and ironwork. He built it from 1956-1979, finishing a year before his death. Maze-like passageways, balconies, and tiered seating surround a stage where a large, steam-powered juicing machine sits. McKissack imagined thousands of visitors would come to see the orange juicing show one day. The day we visited we had the whole park to ourselves.

You can’t just look at pictures of these places. The magic of these holy places is actually being there: the grounds, surrounding landscape, resourcefulness, vision, will, and perseverance all coming together for creation—art springing forth from nothing. You can see the hand in the work and imagine yourself making it. This art is untrained. This art says that anyone can make art.

The way the work was made is what makes it special and also endangered. Folk art sites are wild and subject to the elements. After their creators die, they must be maintained or they fall by the wayside.

Each site we visited was a singular artistic vision come to life, often representing a lifetime of work and self-appointed purpose outside of social norms and capitalism. Sometimes there was help from family, but most of the sites we visited were built in solitude over many, many years in spaces that were also the artists’ home. They lived their art and did things their own way. I believe each artist who created the places we visited envisioned an audience, but the drive to create the work was independent of outside validation. Maybe what makes them the most endangered is living in a world needing constant instant validation.

These spaces were made to broadcast messages to the world, at times channeling messages directly from the heavens, or as a humble reminder to “look at your trash,” which is a divine message indeed.

Like our friend Silvio said, “There is…much more than materialismo.”

Some other folk art sites we’ve visited:

Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens // Philadelphia, PA

Porter Sculpture Park // Montrose, SD

Dr. Evermor’s Forevertron // Sumpter, WI

Prairie Moon // Fountain City, WI

James Tellen Woodland

Sculpture Garden // Sheboygan, WI

Thunder Mountain Monument // Imlay, NV

S.P. Dinsmoor’s Garden of Eden // Lucas, KS

Wonder View Tower // Genoa, CO (under repair)

Nola Tree House // New Orleans, LA (gone)