Outsiders // Episode 02: Jason Lytle

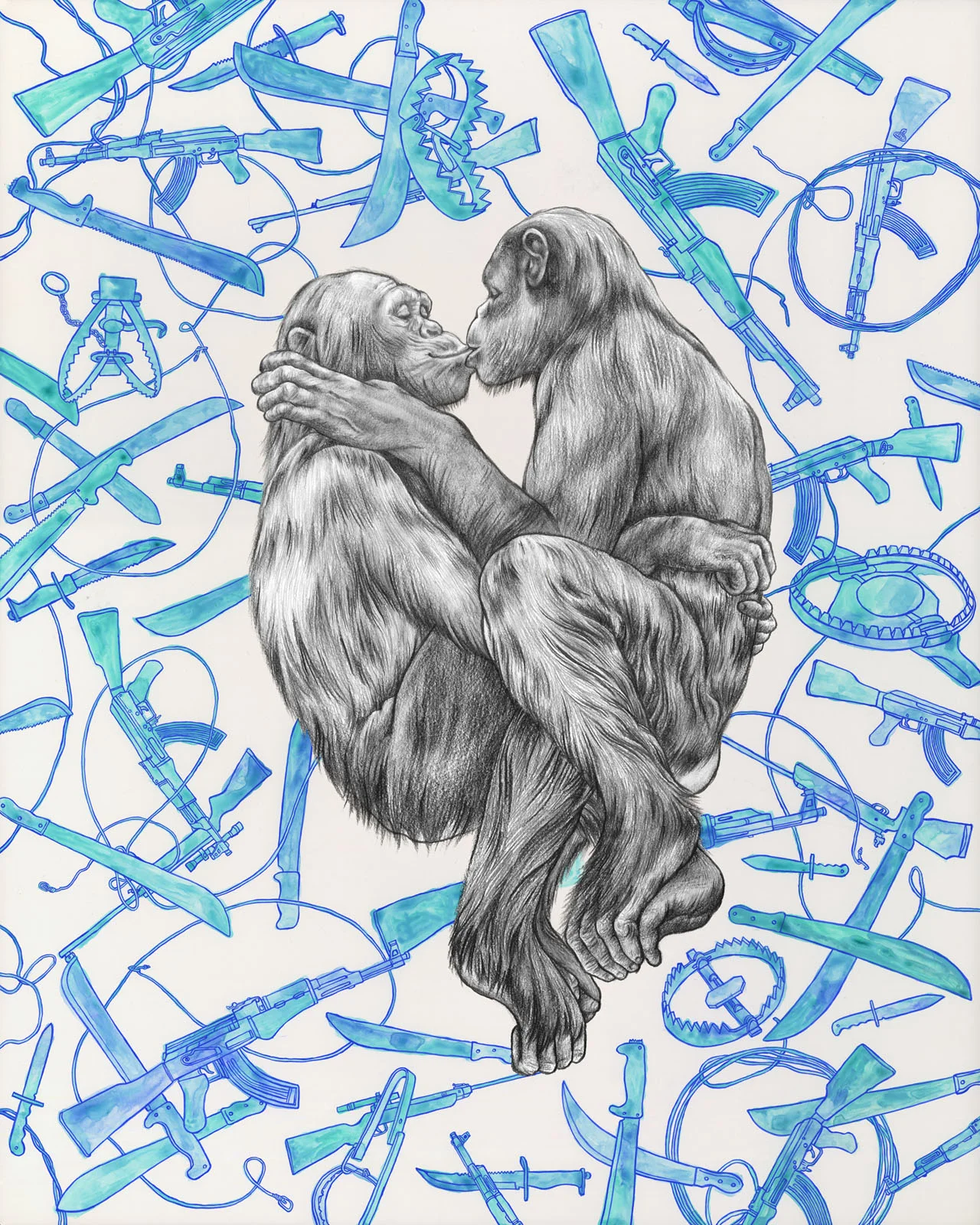

Stay Wild

We asked Jason Lytle of the band Grandaddy for an interview, and he took us trail running on a secret route he named The Edward T. Knobhover Mechanical Engineering Educational Trade Air Conditioning School Trail.

“There’s almost like this spiritual quest level to it, where you go through all these ups and downs, these journeys from the beginning of the trip to the end of the trip.

Running in the woods… it’s pretty wild, literally. It’s as ‘back to caveman’ as you can get.

Keeping steady, keeping at it. You get different magical results than you would from the ‘flash-in-the-pan’ sort of thing.

I think I’ve adopted this trail running thing because it’s teaching me to slow things down, to not be aware of the clock, and to go into some other realm. It’s really similar to why people are drawn to meditation, why people become really dependent on meditation to survive in the modern world.

The only reason I’m making another record is because I’m pretty convinced I’ve got a cool thing to offer in the name of Grandaddy. I’ve got one last project up my sleeve.

I love recording as an art form. The recording is like the beautiful painting, and playing live is just like this hasty sketch. Every night you’re just doing this sloppy fucking sketch of the painting you already perfected.

I don’t know what’s next. I’m just going to try to spend more time outdoors. My mom is getting old. She lives outside of Carson City, NV, and—I really like the high desert and the Sierras—so I’m thinking of going to help her out for a little while.

My home town, Modesto, CA, was kind of world famous there for a while. It had this tire fire that had been burring for months and months and months, and they couldn’t put it out. They just had to let it put itself out.

It’s not like the music is going to go anywhere. I’d just like to play the piano and spend time outdoors.”