The Road Home

Stay Wild

Story by Madeline Baars // @madelinebaars

Photos by Juliana Johnson // @juliana_johnson

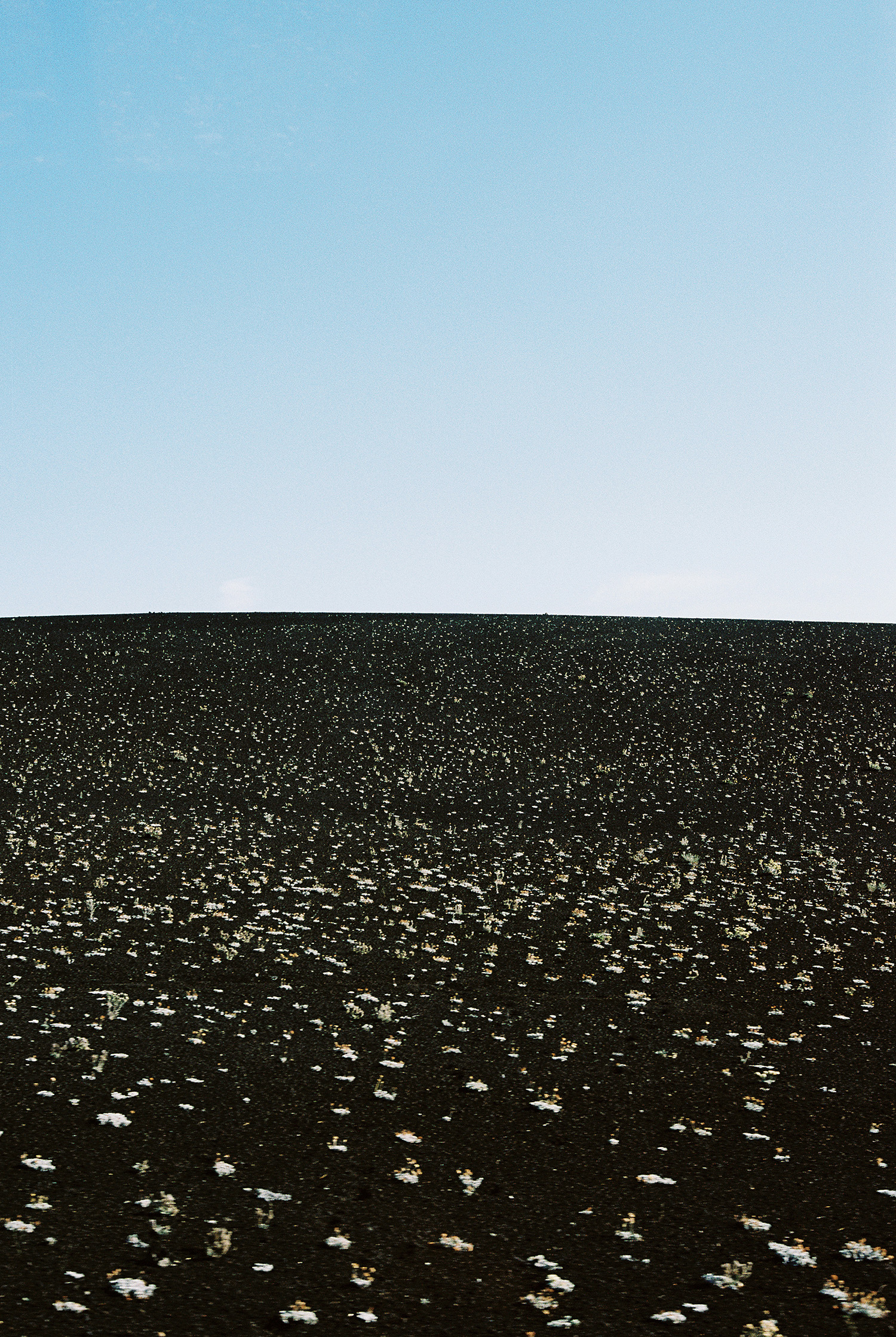

We happened upon it by accident. Looking for lunch, we got caught on a long, dusty road off the highway. Four hours northeast of Phoenix in rural Arizona—pretty sure it’s labeled the Middle of Fucking Nowhere on the map—is a 200 million-year-old petrified forest. The Petrified Forest National Park, to be exact.

A row of broad-chested brown horses were lined up in the parking lot, saddles making it clear they were Property of the U.S. Government. A plethora of signs told us to please, for the love of God and country, leave the park behind. DO NOT POCKET NATURAL WONDERS! THIS IS A FEDERAL CRIME, PROSECUTED TO THE FULLEST EXTENT OF THE LAW! THIS SERIOUS OFFENSE IS PUNISHABLE BY FINES OR JAIL TIME!

To be fair, pieces of a petrified forest make irresistible souvenirs: ancient trees frozen in time, broken into chunks of swirling, solid quartz. If you hold them up to the light, you can see the mineral deposits that run through them in unique patterns—brightly colored stripes, glittery primaries and pastels. It’s so hard to resist. I learned later that it is one man’s job to prevent Triassic theft. He is dressed in plainclothes, and blends in among tourists, watching them slip bits of petrified trees into pockets and pants cuffs. He’ll take them aside in the parking lot, write tickets, confiscate the contraband. Piece by piece, the park loses one ton of petrified wood to quick-fingered tourists every month. These relics are irreplaceable.

“Just take some sage,” my mom whispered to me out of the corner of her mouth. It was some good-looking sage, and seemed like a far lesser crime. I obliged, picking a small sprig in the parking lot, where it sprouted through cracks in the asphalt. That one strand of sage rode on the dash for the rest of the trip, drying and then curling, a tiny and pungent federal offense hiding in plain sight.

Later, we witnessed the sun rising over the majesty of the ancient purple, red, and orange craters of the Grand Canyon, with only a handful of European tourists and their selfie-sticks to keep us company. Seeing the canyon was a lifelong dream, and it was a transcendent morning, hours spent in a place unlike any other in the world.

It was an experience that took our breath away, profoundly overwhelming us. We might as well have been on the surface of Mars. The informational video made us both cry quietly, in the safety of the dim theater, listening to Tom Hanks’ voice.

We hiked along the side of the canyon, carefully climbing out onto the viewpoints that jutted out from the trails, rusty metal railings our only protection from a fall that promised to be long and fatal. My knees shook. We wandered the park for hours, almost entirely speechless. We kept returning to the parking lot in between views of the Grand Canyon, the asphalt providing us with an emotional palate cleanser.

We left the Grand Canyon at lunchtime, and then drove all day. We wound our way around the South Rim, stopping at viewpoints to take in its glory. Along the road, we spotted a big buck. His antlers were giant, velvety and brown, two and three and four branches that rose higher and higher, the tips floating many feet above his head. It was unclear how he could even move with antlers that large, but he seemed happy, quietly munching away. His antlers were beautifully symmetrical, and far, far larger than any we’d ever seen. What a good life he must live, we thought. No fighting with other bucks, no danger from hunters. We hoped he knew better than to ever leave the park.

Soon after, we hit thunderstorms. The dusty hills reflected the sky’s dark grays and purples, cut with shards of lightning like a sharp knife. The clouds were low and angry, and we could see the storm rolling toward us in the rearview mirror. The universe was closing in on top of us, and it was suddenly dark as night in the back window, through the sunroof, and in the world unfolding in front of us. I turned the brights on, gripped the steering wheel, rain beating the windshield and body of the car. We turned the radio off, as if that might help. I didn’t say it, but I was scared shitless. My knuckles were white, my breathing became irregular. Mom sat stiffly in her seat and closed her eyes tight, both hands clasping the passenger-side handle, her face sallow and pale.

An 18-wheeler popped a tire ahead of us with a loud crack that rang out like a shot. It was a sound so loud it affects your other sense—leaving a taste of metal in your mouth, your fingertips numb, an electric shock to the heart. The force of the tire popping and the sudden loss of speed had shredded the hood of the truck, and through the rain, we saw that the truck no longer looked white, but chewed up and blackened. Pieces of tire rolled across the highway like tumbleweeds. I couldn’t avoid them, and my body tensed as we rolled over it, rubber banging the bottom of our car. Just as quickly as the storm had come, it passed and we drove on.

By evening we’d been driving up and down winding, small highways for hours, and we were bone tired. We pulled into Zion National Park right before nightfall. We’d forgotten it was one of the great wonders of America, and not just a $25 fee and a pink mark on the map, a roadblock in between where we were and where we needed to be. We pulled our car into the park, ready to bat our eyes if necessary. We peered up at the ranger, perched in his station, and asked, “Is there any way for us to just get around the park and be at our destination before dark?”

He blinked, not understanding the question. It was one he’d probably never heard. He just shook his head, took our money, and handed us a map of Zion. We drove through one of America’s most splendorous wonders, mouths agape. We rolled our windows down and inched our way through, cruising around its craggy corners as slowly as we could. We heard the sound of wobbly white baby mountain goats bleating on the rocky cliffs, and could see them in the distance following their mothers, balancing on spindly legs and stopping to chew the brush dotting their path. Tourists wandered the park in hiking shoes tied too tight, packs of children in tow. They had come great distances, some many thousands of miles away, just to see this place. We stopped to use the bathroom and buy postcards, and then we moved on. I decided to always look forward and never look back.

Along the Arizona/Utah border, we passed a herd of domesticated buffalo. We sailed by, me craning my neck across the single-lane highway.

“Shit! Mom! Buffalo!”

“Well, what are you doing? Pull over.”

This was my favorite version of my mom, when she was relaxed and unhurried, ready for adventure. When she’s happy like this, the whole world lights up her face. She’s ready for mischief and learning, ready to see the world. And so we pulled the little car over into a rolling, grassy ditch.

I ran 30 feet along the large white fence, just to marvel at the herd of buffalo: mamas and papas and tiny baby buffalo, necks naked and heads unadorned, nudging at their mothers’ sides. They were too far away to take a photo, so I just stood there, across the field, arms draped loosely over the fence posts. I was forced to just experience it, breathe it in, commit what I was seeing to memory. There is something majestic and sad and distinctly American about buffalo, and they stir up feelings: wanderlust, openness, a nostalgia for something I’ve never known. An urge to roam the wide wild plains that once existed, tumbling across an untamed land.