Kalapana Kollars & Anuhea Yagi

Standing in a parking lot with asphalt laid right up to its roots, a 300-year-old breadfruit tree drops giant leaves onto parked cars. This tree has been growing in this place since long before the first European stepped foot on the island of Maui. It’s the last of an ancient grove of ‘Ulu trees planted as a seed bank in the royal orchard of Lele. Yet, this living monument to Hawaiian culture is overlooked by both visitors and locals in Lahiana.

I’ve climbed old town Lahaina’s banyan tree, I’ve surfed the harbor wall break, I’ve bought new slippers and used records here, but I had no idea I was walking above the capital of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i (1830-1845). Long before visitors like me came to chill in Old Lahaina, Hawaiian royalty used to chill in Malu ‘Ulu o Lele (the breadfruit grove of Lele).

Kalapana Kollars explains: “When you learn Hawaiian, you get x-ray vision to the land.” With Maui Nei Native Expeditions, a nonprofit cultural educational program of Friends of Moku‘ula, Kalpana and Anuhea Yagi took me on a walking tour through their historic home. As we walked and talked, the conversation ranged from how Hawai’i was illegally annexed by the US government to how we all grew up listening to the same gangsta rap.

Kalpana and Anu bridge the cultural gap between with Dr. Dre and King Kamehameha. I used to work with Anu at the local alt-weekly, Mauitime. She’s interviewed movie stars, musicians, and pop-culture icons from around the world who came to do their thing and party on the island she grew up on. Anu introduced me to Kalapana at the ‘Ulalena show he has performed in as a musician and dancer for over 16 years. They are two of the most creative people I know on the island.

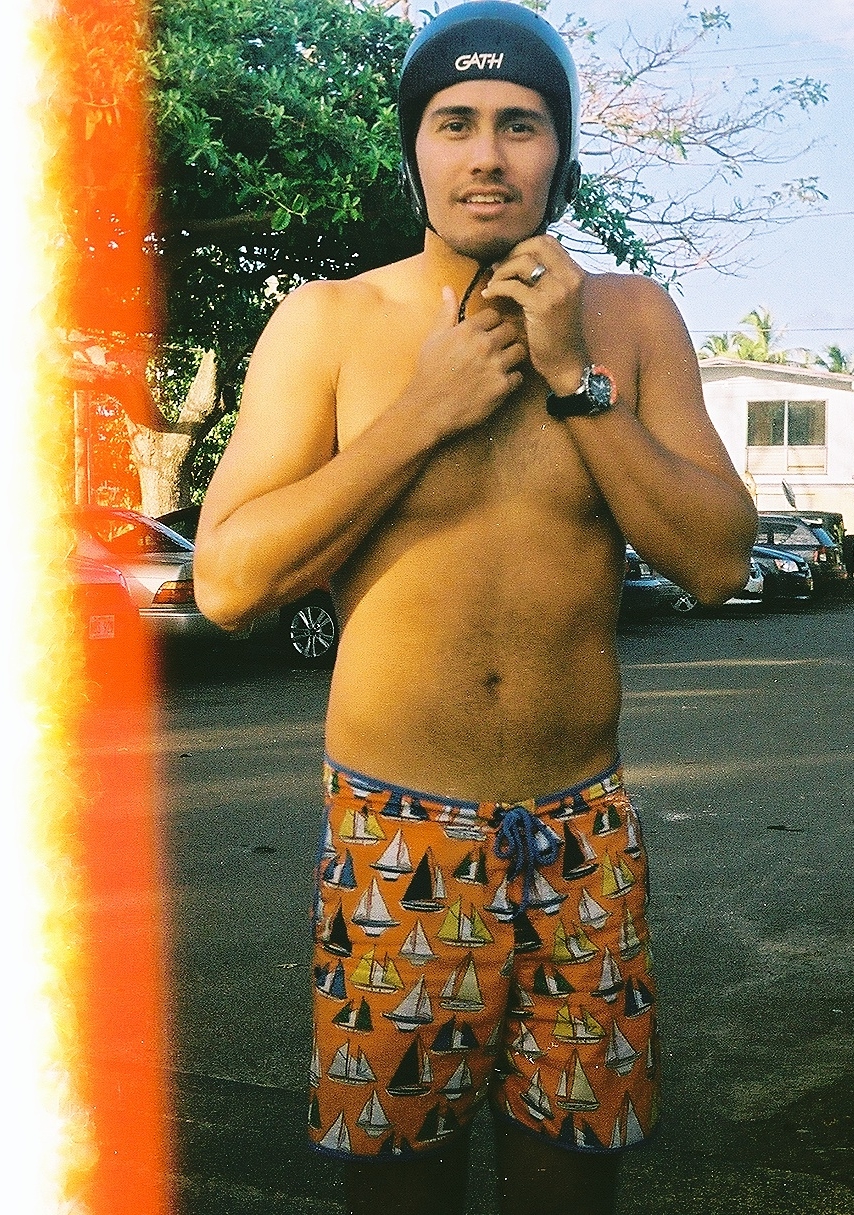

We met up one morning in the sandy beach park of Wahikuli outside Lahaina to pick up trash, and they brought snorkeling gear. Picking up trash for them means going into the ocean and removing fishing line, old rusty hooks, and plastic toys from the reef, along with picking up chip bags from the parking lot. They care deeply about the place they belong to. In talking to Kalpana about being Hawaiian, he says, “It’s not about ethnicity, it’s about nationality. It’s about home.” In other words, you don’t have to be Hawaiian to be Hawaiian, you just have to help care for and preserve this place.

In their living room, Anu shows us some of the trash treasures (trashures?) she’s found in the reef, while Kalpana plays music on one of the ʻohe hano ihu’s (Hawaiian nose flutes) he’s carved. Kalapana learned to carve and play them from a friend who recently passed away. By playing for us, he is keeping the cultural tradition and memories of his friend alive. I saw Hawaiian words taped to the ceiling fan, the fridge, and the computer. These tiny taped words translate the modern devices into Hawaiian in an effort to “relearn histories that where forgotten.”

Kalapana goes on to say that, “To heal ourselves is to heal our ancestors.” Much of their cultural heritage was paved over when waves of missionaries came to civilize the natives by imposing imported culture. In fact, the wave of imported culture never really stopped. It comes with gangsta rap, it comes in chip bags, and it’s still coming. The only thing keeping the asphalt from killing the last ‘Ulu tree of the royal Lele grove are people like Anu and Kalapana.

mauinei.com // ulalena.com