Thoughts on Mountains and Love

Stay Wild

Story by Charlotte Austin

Photos by Rodrigo De Medeiros

The first thing I learned to love about the mountains was the sharpness of cold water on my tongue. I loved that cutting burn immediately—a painful gulp that felt like truth—and I knew that I could not live without something that was so honest inside my chest.

When I am guiding, every morning starts the same: I wake up, bundled in layers of down, and wriggle one arm free to reach for my Nalgene. Bracing the bottle between my knees, I crack the ice that has frozen the bottle shut, shake it hard to make the ice-slush drinkable, and put my mouth to the rim. The taste is glacier ice, chopped into chunks the day before with my battered axe and melted just to liquid over a wobbling white gas stove. I am careful to keep it from touching my teeth, instead sliding it straight to the back of my throat and feeling it burn down the inside of my chest and deep into my belly.

Then there is a shuffle while I find a headlamp, cram my legs into long underwear, and stuff my feet into boots that have frozen solid overnight. There is the slow unzip of the tent door, the careful setting of the bottle onto the snow, the flustered ejection of a girl onto the cold glacier.

When I uncurl my body to stand, it is into air that is colder than the water in my belly. The first thing I notice is that—no matter what time it is—the snow reflects enough light to read a newspaper. It is painfully beautiful: a cold gray-blue light on a harsh, angled landscape of glacier and starlight. I stand still and breathe, letting the cold sink deep into my skin. Sometimes I listen to the wind rustle the nylon of the tents nearby; sometimes there is silence. I stoop, lift my water bottle from the snow, and take another long sip of cold water.

This is how I first learned to love the mountains.

When I see a man who works in the mountains look at his body in the mirror, it reminds me of the way a driver would look at a race car. I loved one once—a man—who would run his hands over every inch of his own body: his battered feet, his sinewed thighs, his flat abdomen, the coiled muscles of his ass. He squinted at the wrinkles in the skin, the scabs on the tips of his pinky toes, the tendons around his knees that were visible in his thighs. It was part of his morning routine: He’d lay on the floor of the shower, letting water scald his body, then walk, still dripping, to the mirror to assess his naked reflection. He knew every cell, every blood vessel, every hair. At any given time, he could tell me his heart rate and blood oxygen levels just by closing his eyes. His profession was climbing the world’s most dangerous mountains, and he needed to know exactly what he could and what he could not do.

His self care was precise. Inputs and outputs were carefully assessed: grams of protein, hours of sleep, the color of his urine. He stretched every night, opening his hips and breathing deeply. When he touched his own body, it was with reverence. But when we were out in town—which was rare—he never looked at his reflection in a window. He was undeniably a striking physical specimen, which he knew in an absent-minded, objective way. But he didn’t need to admire his appearance—only to know intimately the machine that was his body.

When I started guiding, I did not treat my own body with that kind of care. I’ve been climbing mountains for years now, but I still don’t know if it’s possible for a woman to love her own body in that matter-of-fact way.

People who don’t climb ask what it’s like to find yourself on a mountain. They imagine a spiritual place, some ethereal journey bookmarked with prayer flags and picturesque Sherpa children and lean, wind-hardened people gazing into the distance wearing name-brand parkas. You don’t find yourself on a mountain, I tell them. Mountains are beautiful and harsh and wild, yes, but mountains are also both more and less than most people imagine them to be.

When you reach a summit, you only find the things that you have carried with you. To get to the top of a mountain, you will bleed and sweat and cry, maybe mark each switchback with a small puddle of vomit in the snow. You’ll lose things along the way, dropping them down a slope or choosing to leave them behind. But when you get to the top, you’ll reach into your backpack and you will know that there are things that you have carried with you through the night. And you will love deeply the things that have survived that journey.

Once, at the ripe end of a September, I took a friend to a town at the base of a mountain. He was a city man, visiting to take photos of strong young men. After a day of shooting, we sat on picnic benches with pizza and cheap beer and talked about a calendar that is produced every year.

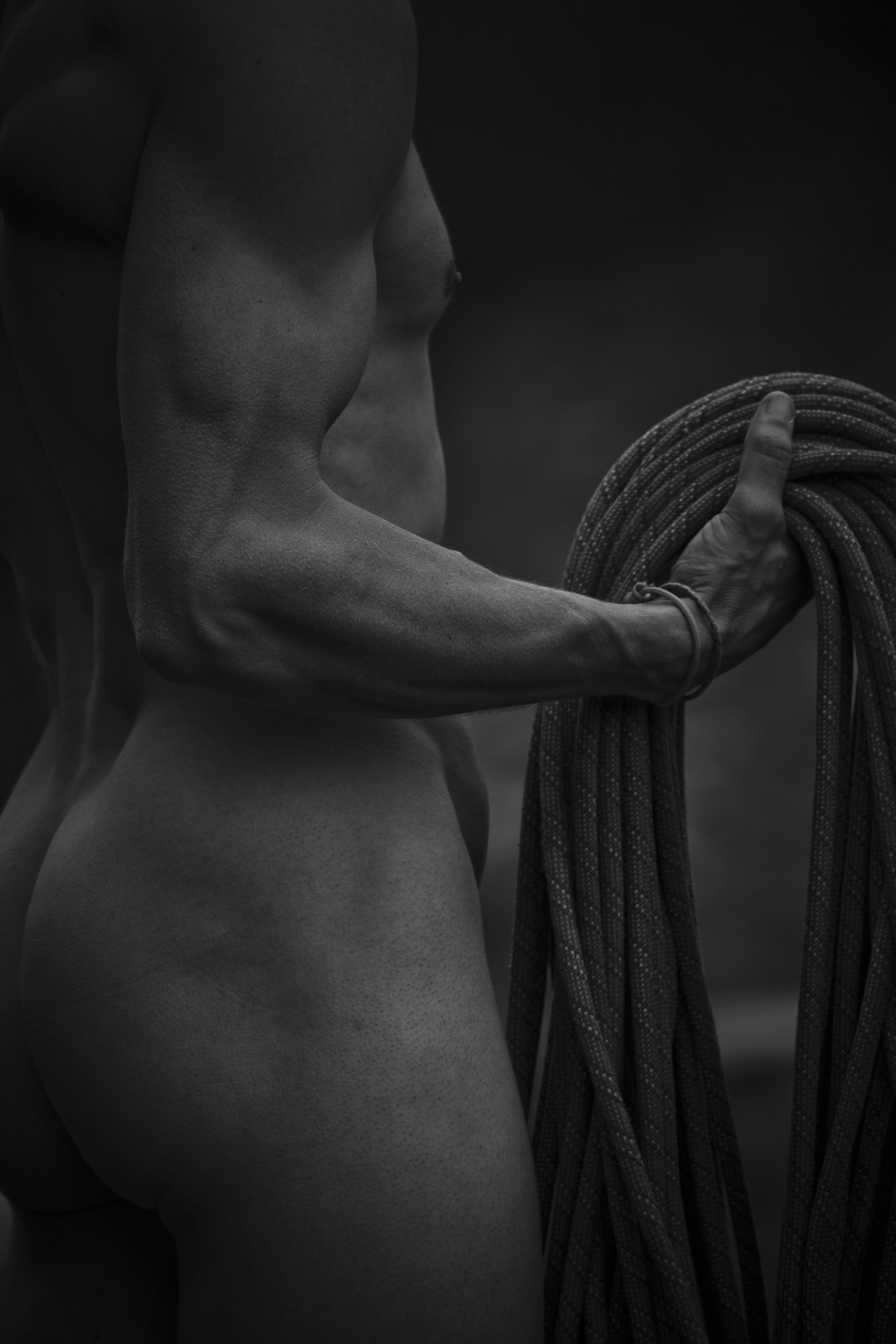

The calendar features twelve glossy panoramas, each month a different photo in high-contrast black and white. The man who produces the calendar every year goes to some of the world’s best climbing destinations: Yosemite, Joshua Tree, Red Rocks. He shoots young women climbing, nude skin against rock. The juxtaposition of strong bodies against hard stone is beautiful, and every year the calendar sells out.

Word on the street is that he tried to make a male version, but nobody bought it. Apparently men’s bodies are different. The photographer and I talked about that for a long time as we sat in the sun that day. “You have to be willing to love a body to shoot it well,” he said. “Your lens needs to fall across the skin like light.”

I knew exactly what he was talking about.

At the end of a guiding season, there is a process. First I sleep: My body is wrecked, broken down. I am calorie-deficient muscle with a sunglasses tan, and I want nothing more than to watch Modern Family and eat fruit that has never been dehydrated. That stage lasts for a week, more or less, depending how long I was in the field.

The next stage varies. Sometimes I want to spend time with my family, hear my father’s stories of adventure and feel my mother’s delicate skin against my sandpaper hands. Sometimes I want to create, and I’ll spend weeks writing and then deleting words as I try to describe the smell of cold air. Other times I want to travel, responsible only for myself.

The final stage is an inevitability: rage. I rage against my home, my partner, my family, my art. I rage against the city lights, and the way they encroach on the perimeter of the sky at dawn. I toss and turn until I rip off my blankets, stumble blindly out of my home, and gulp the cold night air in desperation. I know, then, that it’s time to go back to the mountains. I miss the brutal truth, the purity of my love for those places. I stand on a street corner, out of breath, and look for snow-capped glimpses of freedom on the skyline between the city lights.

For a long time, I loved the men of the mountains. They are simple and elegant, clean in the lines of their bodies and in their motivations in life. The way they know how to love is hard and rough and unthinking, and they keep their lives simple so that they can bend, unobstructed, at the altar of their chosen truth. They sleep in their rusty hatchback cars, eating rice and beans that they call Mexican food, and cut their own hair.

Those men are hard to live with, I eventually realized. They love hard and simply, but they expect their women to be waiting when they come home.

It took me most of my twenties to realize that the thing that attracted me most to those men—their single-minded pursuit of what made them feel whole—was something I wanted to find in myself, not in a partner. Loving that in someone else, I learned, got me close enough to reach out and touch it. But the feel of self-worth deep and cold in my belly was something I needed to earn. I had to carry it with me, no matter the cost.

Sometimes, as we push up a route in the dark in the mountains, a struggling client will ask me a simple question: Why does anyone choose this pain? It’s all imaginary, he will say; summits are arbitrary, and the suffering is too much. I could live my life without this experience. They turn to look in my eyes, blinding me with their headlamp, searching for an answer to their question: Why? I hand them some water, tell them to drink. “I don’t know your truth,” I say, forcing them to breathe. “You may not find yourself here.” Most clients leave it at that, slumping down to put their hands on their knees and pant in the thin alpine air. But some press me, asking why it’s worth it, how I handle the pain and the cold and the ever-raw confrontation with the part of myself that is dark and unblinking and true. And sometimes, every once in a long while, I tell them the truth: I could not live without this fight.