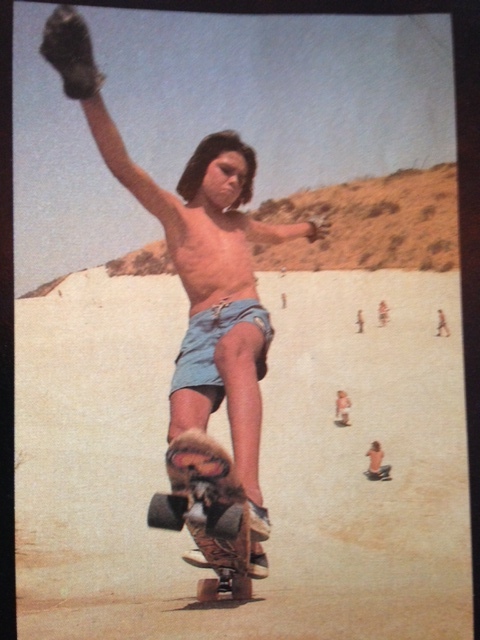

Maker // Shaper

Stay Wild

Shaper Studios is an open work space where anyone can make a surfboard

By Scrappers

The first wave I ever caught and experienced pure stoke with was on a surfboard shaped by Skip Frye. It was the board my brother-in-law let me borrow to paddle out at Sunset Cliffs in OB (San Diego). I had no idea that this shaper was a local legend. I had no idea that he shaped this board to surf this exact wave. I had no idea he was the guy picking up trash in the parking lot for everyone. I had no idea how much love, intention, and skill went into the board that got me hooked on surfing.

When you don’t know what goes into making a thing, it’s hard to respect the people who make it. Shapers get respect, though. They are the old wise Zen masters that every surfer respects. They are the makers of the craft that a whole culture evolved from.

Shapers are special people, but anyone can be a shaper. Heck, it’s just making a toy to play with in the ocean! Anyone can do it. Most of us just lack the tools, the workspace, and the know-how. Or if we have the know-how, we lack the tools and workspace.

Surfboard-making is a messy and expensive business. Whether you’re making it out of wood, foam, or an eco-friendly material, it’s super messy to cut, sand, and glass. You need a special workspace with exhaust vents, special lighting, a weird work table, and some pricey tools. There are a lot of obstacles, but the obstacle has become the opportunity.

Shaper Studios has created an open DIY studio workspace where anyone can make a surfboard. They teach workshops for people who want to learn super basic stuff and super advanced stuff. If you already know how to shape, they provide all the tools and work space you’ll need, along with a membership. It’s pretty smart, eh?

Shaper Studios started in North Park, San Diego, but have since opened shops in other towns like Costa Mesa, and other countries like Canada and Chile. Their brilliant idea is spreading because it’s open to everyone. Turns out a lot of the people who sign up for the classes don’t even surf. They just want to make something cool with their own hands.

We can all be wise Zen masters who earn respect and share stoke with the different boards we make.