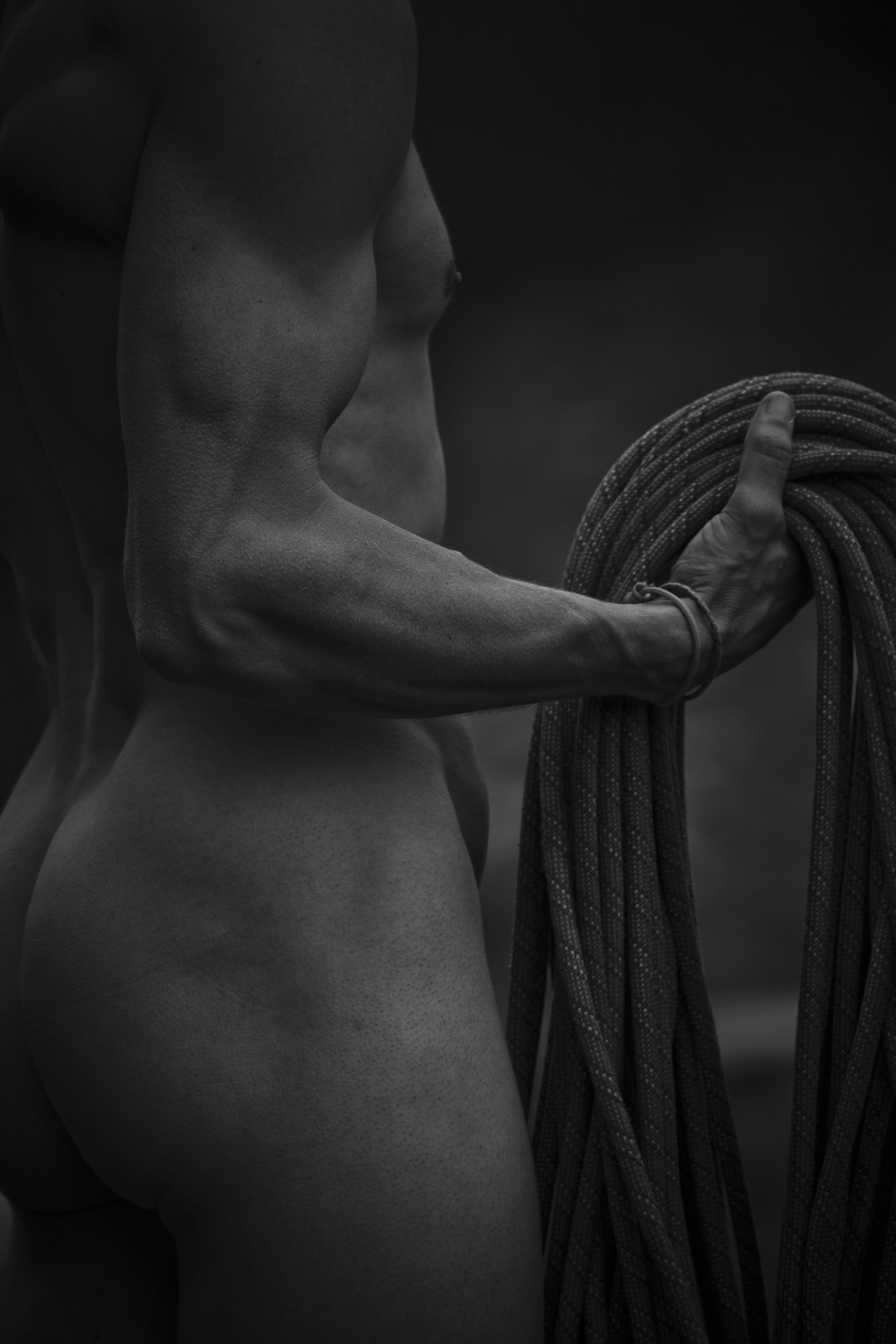

The first thing I learned to love about the mountains was the sharpness of cold water on my tongue. I loved that cutting burn immediately—a painful gulp that felt like truth—and I knew that I could not live without something that was so honest inside my chest.

When I am guiding, every morning starts the same: I wake up, bundled in layers of down, and wriggle one arm free to reach for my Nalgene. Bracing the bottle between my knees, I crack the ice that has frozen the bottle shut, shake it hard to make the ice-slush drinkable, and put my mouth to the rim. The taste is glacier ice, chopped into chunks the day before with my battered axe and melted just to liquid over a wobbling white gas stove. I am careful to keep it from touching my teeth, instead sliding it straight to the back of my throat and feeling it burn down the inside of my chest and deep into my belly.

Then there is a shuffle while I find a headlamp, cram my legs into long underwear, and stuff my feet into boots that have frozen solid overnight. There is the slow unzip of the tent door, the careful setting of the bottle onto the snow, the flustered ejection of a girl onto the cold glacier.

When I uncurl my body to stand, it is into air that is colder than the water in my belly. The first thing I notice is that—no matter what time it is—the snow reflects enough light to read a newspaper. It is painfully beautiful: a cold gray-blue light on a harsh, angled landscape of glacier and starlight. I stand still and breathe, letting the cold sink deep into my skin. Sometimes I listen to the wind rustle the nylon of the tents nearby; sometimes there is silence. I stoop, lift my water bottle from the snow, and take another long sip of cold water.

This is how I first learned to love the mountains.